Vai al Contenuto Raggiungi il piè di pagina

RETROSPETTIVA: "1968, diario del mio viaggio con destinazione terremotati del Belice"

Un medico in pensione, Nicola Di Pietro, 54 anni dopo racconta la sua esperienza di soccorritore improvvisato. Tra difficoltà e rischi per la propria vita, ma una sola parola d’ordine: "indietro non si torna"14/02/2022 09:08:29

MESSINA - Quattro giorni dopo il terremoto del Belice, che avvenne la notte tra il 14 e 15 gennaio 1968, due studenti liceali di Villafranca Tirrena e Milazzo, in provincia di Messina, stanno per mettersi in marcia per raggiungere la gente di quei territori.

Avevano riempito di beni di prima necessità, frutto di donazioni spontanee di semplici cittadini e persino di una nota farmacia di Barcellona Pozzo di Gotto, ogni angolo di un furgoncino messo a disposizione dal papà di uno di loro. Partiranno di notte per non incappare nelle maglie della Polizia locale, che non vedeva di buon occhio tale iniziativa, e con in mente le raccomandazioni del preside del loro liceo e l’incoraggiamento di compagni di scuola, concittadini e genitori.

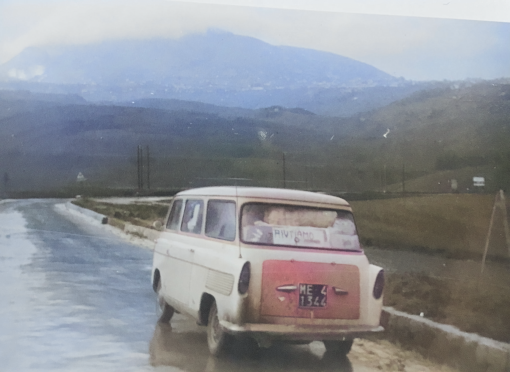

Come Nicola e Ciccio, tanti altri giovani e meno giovani, in quel triste gennaio del 1968, erano in procinto di partire o stavano immagazzinando generi alimentari e vestiti per la stessa destinazione. Tutto era frutto di moti spontanei, privi di precise istruzioni e, talvolta, solo tollerati dalle istituzioni dell’epoca. Oggi sappiamo che ogni soccorritore, anche per svolgere la propria missione di volontariato, deve avere mezzi idonei, adeguata formazione e una struttura di coordinamento istituzionale alle spalle. In mancanza di questi fondamentali, anche il semplice viaggio di due ragazzi neopatentati a bordo di un furgone può diventare un’impresa rischiosa. E’ ciò che si evince, tra l’altro, dal racconto sul filo dei ricordi che cinquantaquattro anni dopo ha scritto per noi uno dei due studenti protagonisti di quell’iniziativa. Si chiama Nicola Di Pietro, oggi è un medico universitario in pensione e vive ancora a Villafranca Tirrena. A corredo di questa sorta di diario ci sono anche le foto del “Viaggio destinazione terremotati del Belice”; immagini in bianco e nero, oggi colorate digitalmente per apprezzarne meglio i dettagli.

Quindi quello che proponiamo è un breve reportage inedito e indipendente, sotto forma di testimonianza diretta del nostro passato più drammatico.

Francesco Venuto/DRPC Sicilia

In viaggio con destinazione popolazioni terremotate del Belice

Venerdì 19 - sabato 20 gennaio 1968

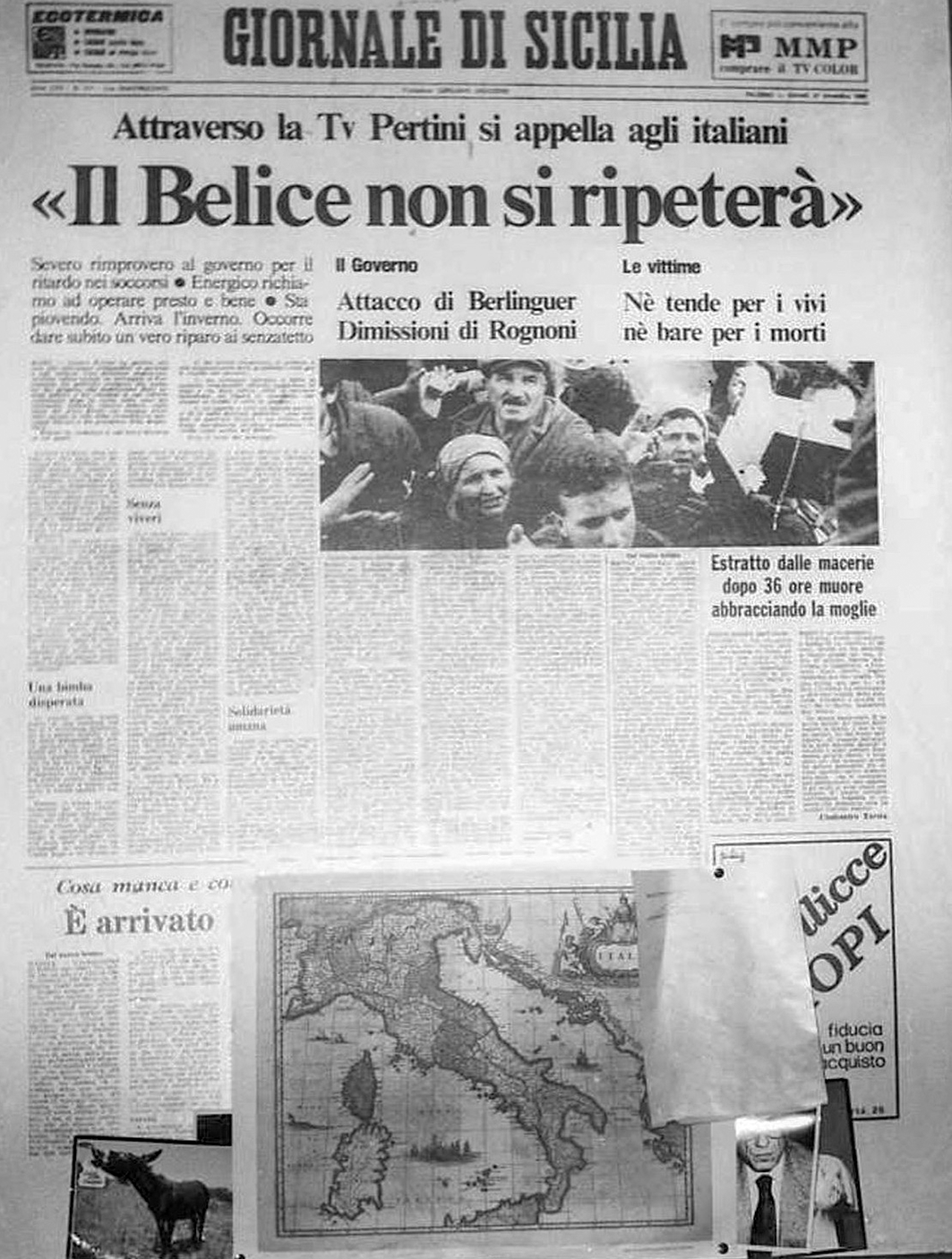

«Nella notte fra il 14 e 15 gennaio 1968, il giornale radio annunciò il terremoto nelle terre della Valle del Belice, terre che comprendono le province di Trapani, Agrigento e Palermo. Magnitudo 6,4 (X scala Mercalli, quasi 400 i morti (fra i quali 10 soccorritori), 1000 i feriti, 90.000 gli sfollati.

Io frequentavo il quinto anno del liceo scientifico Luigi Valli di Barcellona Pozzo di Gotto e viaggiavo tutti i giorni da Villafranca con il treno; a Milazzo salivano a bordo due miei compagni di classe (Ciccio Basilicò e Vincenzo Caravello). A scuola con tutti i compagni decidemmo di fare qualcosa per i terremotati. Il preside, informato della nostra iniziativa, ci raccomandò di fare tutto con la massima attenzione. Anche a Villafranca si sparse la voce dell’imminente mia partenza e la gente del posto portò generi di prima necessità. Era venerdì 19 gennaio e l’indomani a Barcellona la scuola sarebbe stata chiusa per la festa del Patrono San Sebastiano.

Nel pomeriggio sono partito da Villafranca col furgoncino Fiat “Sabrina” carrozzato Fissore di mio padre. Passai da Milazzo a prendere Ciccio Basilicò e, giunti a Barcellona, in fretta e furia caricammo il furgone con gli altri sacchi di beni raccolti in quella città, in parte donati anche dai genitori farmacisti di una nostra compagna di scuola. Eravamo ansiosi di partire anche perché avevamo saputo che ci cercavano i Vigili Urbani per bloccarci e requisirci tutto.

Partimmo verso le nove di sera, pioveva e faceva freddo. Il sistema di riscaldamento del furgone non funzionava, ma questo non era un problema per due giovani pieni d’entusiasmo. Il nostro mezzo era stracarico al punto che la seconda ruota di scorta con gli attrezzi aveva trovato posto fra le gambe di Ciccio. Dietro di noi un carico che comprendeva 100 kg di latte in polvere e condensato, borotalco, omogeneizzati, zucchero, pannolini, scatolette varie, 100 kg di pane, cappotti con le tasche piene di caramelle, scarpe.

Appena fuori Barcellona, lungo la strada statale, abbiamo rischiato di morire: prima di Falcone, su un lungo rettilineo, mentre sotto la pioggia battente eravamo in procinto di attraversare un passaggio a livello ferroviario con le sbarre alzate, ci accorgemmo appena in tempo che stava transitando un treno merci appena illuminato dai fari del Sabrina. Fortuna volle che viaggiassimo a bassa velocità e i freni del furgone, nonostante il carico, funzionarono a dovere. Caustico il commento in dialetto del mio compagno Ciccio, ancora scosso per lo scampato pericolo: “bbonu cuminciamu (iniziamo bene)”.

Facemmo rifornimento di benzina a Palermo, in una città deserta perché anche lì era arrivato il terremoto. Un guasto alla dinamo ci costrinse a cercare aiuto presso una concessionaria Fiat, che era ubicata lungo la salita per Monreale. Aspettammo (al freddo e al gelo) l’apertura dell’officina della concessionaria e, sistemata provvisoriamente la dinamo, riprendemmo il nostro viaggio.

Le scosse di terremoto continuavano ed ogni tanto percepivamo qualcosa anche noi. Sul nostro furgone c’era montata un’autoradio “Autovox” grazie alla quale ci tenevano aggiornati su quello che stava succedendo. Di notte trasmettevano in onde medie il programma “Notturno dall’Italia” e in quei frangenti ascoltavamo spesso i conduttori annunciare che c’erano “numerose autocolonne con i soccorsi in movimento verso le zone terremotate”. Noi, però, non vedevamo nessuno, tanto che Ciccio si fece assalire dai dubbi, sintetizzandoli con una frase ripetuta in più occasioni: “vuoi vedere che abbiamo sbagliato strada...”. Ma “indietro non si torna…”, ce lo ripetevamo come se fosse un mantra, nonostante viaggiassimo lungo strade deserte, paesi svuotati, con il freddo che ci metteva a dura prova e la pioggia che quasi mai ci aveva abbandonati. Ciccio accendeva la sua pipa con tabacco aromatizzato, “Glen”, profumatissimo. Bastavano un paio di “tirate” ed il nostro furgone si riempiva di “nebbia dall’odore gradevole” e l’effetto illusorio del fumo di un caminetto. Durava poco, perché il freddo e l’umidità impedivano alla brace di rimanere accesa.

Giunti in prossimità di Alcamo, nuovo problema al motore, stesso componente difettoso: la dinamo, la cui spia rimaneva accesa. Entrati in paese, ci mettemmo alla ricerca di un elettrauto: ne trovammo uno che aveva l’officina nella piazza principale. Nel grande spazio c’era gente silenziosa, coperta da pesanti mantelli o cappotti con i baveri rialzati a protezione delle orecchie e berretti neri ben affondati sulla testa. Poi ci spiegarono che nelle case nessuno si sentiva al sicuro, perché le scosse di terremoto continuavano e il timore di possibili crolli era più che fondato. La paura si leggeva nei volti, nei silenzi e nello smarrimento di quelle persone.

Nonostante il nostro turbamento, tra quelle persone rintracciammo il titolare dell’officina, gli spiegammo quale fosse il problema e per risposta fece spallucce: non poteva fare nulla, perché aveva paura che l’officina, ubicata in un vecchio edificio in pietra, gli potesse crollare addosso. Poi, quando l’elettrauto vide il nostro furgone stracarico di aiuti e comprese il motivo del nostro viaggio, cambiò atteggiamento rassicurandoci: “non preoccupatevi, in qualche modo faremo...” Sollevò la saracinesca, entrò di corsa in officina, prese i ferri necessari e poi si mise al lavoro, al sicuro, nella stessa piazza. Quando non era chinato nel cofano motore, armeggiando con cinghie e componenti elettrici, era perché doveva rientrare in officina per prelevare qualche ricambio e sempre di fretta. Finito il lavoro, ringraziandolo chiesi di pagare. “Niente”, rispose, “ Non mi dovete nulla”. Il suo lavoro, ci spiegò, era da considerare il suo piccolo contributo al buon esito del viaggio.

Il viaggio poteva ricominciare, con la fiducia ritrovata e la presa di coscienza delle responsabilità che ci stavamo assumendo anche semplicemente con il passaggio del nostro piccolo furgone con la scritta “Aiutiamo i terremotati”.

Attraversando le zone colpite dal terremoto, vedevamo greggi di pecore che vagavano per le campagne senza pastore, abbandonate; vedevamo le spallette dei ponti crollate e macerie, tante macerie; ad un certo punto ci siamo imbattuti nell’ennesimo ponte crollato. Qualche macchina, con grosse difficoltà attraversava il torrente sottostante. Aspettammo un po’ e poi decidemmo di attraversarlo anche noi. Non so come abbiamo fatto, ma ci siamo riusciti, con Ciccio che era sceso per suggerirmi la manovra migliore. Raggiunta la statale, dopo qualche centinaio di metri, abbiamo forato uno pneumatico. Mentre cambiavamo la ruota, si avvicinò un signore che, piangendo, ci chiese dove fossimo diretti. Ci disse che da due giorni cercava i suoi parenti e che non aveva ancora trovato nessuno. Ci salutò, salendo sulla sua Fulvia bianca, raccomandandoci di andare a Santa Ninfa, “perché ancora il paese non aveva ricevuto aiuti”.

Andavamo piano, il furgone era stracarico e con le ruote posteriori disallineate per il peso.

Fatto qualche chilometro, sulla strada in salita, vedemmo un gruppo di persone correre verso di noi. Avevano intuito che portavamo qualcosa: ci fermammo e distribuimmo un po’ di pane, qualche cappotto, scatolame e zucchero. Poi decidemmo di raggiungere la tendopoli di Santa Ninfa e consegnare tutto al personale sanitario.

Lungo la strada ci fermammo ad un abbeveratoio per il bestiame, per dissetarci e riempire una bottiglia d’acqua. Mentre eravamo intenti a fare questa operazione, si fermò accanto a noi una fuoristrada dell’esercito con alcuni soldati a bordo. Parlammo degli eventi e ci dissero che non mangiavano dal giorno prima. Ciccio pensò bene di dare loro la nostra colazione.

Dopo qualche chilometro, percorso tra cumuli di macerie, finalmente arrivammo alla tendopoli allestita su un terreno fangoso. C’era pure un ospedale da campo e qualche istante dopo ci venne incontro una giovane dottoressa che ci chiese cosa avevamo portato. Quando apprese che c´erano latte in polvere e condensato, pannolini, omogeneizzati, zucchero e borotalco (generi indispensabili per i bambini), sul suo viso apparve un sorriso di gioia e ci mandò subito dei ragazzi per scaricare il furgone e portare tutto in tenda. Ciccio, preso dall’entusiasmo, mi disse: “Io resto qui a dare una mano”. Con grande fatica riuscii a farlo desistere e ci mettemmo in viaggio verso casa, progettando di ritornare con un nuovo carico di aiuti.

Quando fummo nei pressi di Capo Calavà, finalmente incontrammo una colonna di camion militari che procedeva in direzione Valle del Belice, con scorta e lampeggianti accesi.

Ciccio dormicchiava e lo svegliai quando raggiungemmo la sua abitazione a Milazzo. Arrivato a Villafranca, erano le nove di sera, nella piazza principale, ad aspettarmi c’erano il parroco, insieme ai titolari di una ditta locale di trasporti, oltre ad alcuni cittadini. Mi chiesero notizie sul percorso che avevo seguito, perché a loro volta stavano per partire e portare beni di prima necessità ai terremotati del Belice. Poi ho saputo che fecero un altro percorso e non raggiunsero direttamente le tendopoli (furono bloccati prima), lasciando comunque gli aiuti presso un centro di raccolta. Con il tempo mi resi conto che forse ero stato tra i primi ad arrivare da fuori provincia sui luoghi del disastro. Questo è probabilmente il motivo per il quale io e Ciccio abbiamo visto macerie, solitudine, tante persone disorientate e pochi aiuti spesso distribuiti in modo irrazionale. Nicola Di Pietro».

*MESSINA – Four days after the Belice earthquake, a sequence that took place between the 14th and 15th January 1968, two high school students from Villafranca Tirrena and Milazzo (two towns near Messina, Sicily) decided to help out the inhabitants of the Belice area.

They had collected essential goods donated by other citizens and a famous pharmacy in Barcellona Pozzo di Gotto, and put them in every available place in a van lent by one of their fathers. They chose to go during the night because the local police were looking for them, not being happy with their decision. But they were sure of what they were doing, keeping in mind the words told them by their principal, their schoolmates, and parents.

Just like Nicola and Ciccio, many other people in that sad January of 1968 had decided to help out those damaged by the earthquake in any way possible. Most of this was spontaneous, and often the institutions did not support these initiatives. Now we know that each rescuer, even when they are doing it as volunteers, must have adequate means of transportation, knowledge on how to help out and be coordinated by institutions. When these fundamentals are not respected, a journey undertaken by two novice drivers on a van can become a risky venture for sure.

And this is what can be understood from the story written 54 years later by one of those same high schoolers. He is Nicola Di Pietro, and today he is a retired physician who still lives in Villafranca Tirrena. On the side, we can now look at the pictures of the “Journey towards those damaged by the Belice earthquake”: originally in black and white, these photos have been digitally coloured to better appreciate the details on those scenes.

This is therefore a tiny unedited and independent reportage on the Belice earthquake, in the form of the direct testimony of our most dramatic past.

Francesco Venuto/DRPC Sicilia

A journey towards those damaged by the Belice earthquake

Friday 19th - Saturday 20th January 1968

«On the night between the 14th and 15th January 1968, the radio newspaper announced the earthquake in the Belice Valley, that includes the provinces of Trapani, Agrigento and Palermo. Magnitude 6.4 (X Mercalli scale), with nearly 400 people dead (including 10 rescuers), 1000 wounded, 90,000 displaced.

It was my fifth year at the “Luigi Valli” lyceum in Barcellona Pozzo di Gotto, and I traveled every day from Villafranca by train; two of my classmates (Ciccio Basilicò and Vincenzo Caravello) boarded in Milazzo. At school, when talking with all the classmates about the earthquake, we decided together that we had to do something for those damaged. The principal, informed of our initiative, recommended we did everything we had to do with the utmost attention. The word about my imminent departure also spread in Villafranca, and the locals brought many essential goods to my house. It was Friday 19th January. The next day, our school would have been closed because it would have been a holiday – it was the day of their Patron Saint Sebastian.

In the afternoon, I left Villafranca with my father´s Fiat “Sabrina” van with Fissore bodywork. I went to Milazzo to pick up Ciccio Basilicò and, once in Barcelona, we hurriedly loaded the van with the other bags of goods collected in that city, partly donated by the parents of one of our school friends, who owned a pharmacy. We were anxious to leave because we had been told that the local police were looking for us to block us and requisition everything.

We left around nine in the evening, it was raining, it was cold. The van´s heating system did not work, but this was not a problem for two young people full of enthusiasm. Our vehicle was overloaded to the point that we had put the second spare wheel with the tools between Ciccio´s legs. Behind us, there was a load that included 100 kilos of powdered and condensed milk, talcum powder, baby food, sugar, diapers, food cans, 100 kg of bread, coats with pockets full of sweets, shoes.

Just outside Barcellona, along the state road, we almost died: before Falcone, on a long straight road with low visibility due to the pouring rain, we were about to cross a railway level crossing. The bars were raised, but we realized just in time that a freight train barely illuminated by the Sabrina headlights was passing. We were lucky to be travelling at low speed and that the van´s brakes, despite the load, had been working properly. I still remember the comment in dialect of my companion Ciccio, still shaken: "bbonu cuminciamu (we’re getting off to a good start)".

We refuelled in Palermo, in a deserted city because the earthquake had arrived there, too. A breakdown in the dynamo forced us to seek help from a Fiat dealership, which was located along the uphill road to Monreale. We waited (in the freezing cold) for the opening of the dealership workshop and, once the dynamo was temporarily fixed, we resumed our journey. The earthquakes continued and every now and then we felt something too. An "Autovox" car radio was mounted on our van, thanks to which we were kept updated on what was happening. At night they used to broadcast in medium waves a radio program called "Nocturne from Italy", and in those moments we often heard the announcers claiming that there were "numerous queues with rescuers moving towards the earthquake areas". We, however, did not see anyone, to the point that Ciccio let himself be assailed by doubts, which could be summarised with a sentence he then repeated numerous times: "vuoi vedere che abbiamo sbagliato strada...". But we also fought them with another sentence: “there is no going back”, which became a mantra at some point, even though we were travelling along deserted roads, empty towns, freezing and with the rain that never left us.

Sometimes, Ciccio lit his pipe full of flavoured tobacco, “Glen”, very fragrant. A couple of "puffs" were enough for our van to be filled with "pleasant-smelling fog", a sort of illusion that this could be the smoke from a fireplace. It did not last long, because the cold and humidity prevented the embers from staying alight. Once we were close to Alcamo, there was a new engine problem, the same faulty component: the dynamo, whose warning light remained on. Once we entered the village, we started looking for an electrician: we found one who had a workshop in the main square. In the large space there were silent people, covered in heavy cloaks or coats with raised collars to protect their ears, and with black hats well sunk on their heads. They told us that no one felt safe in their own house, because the earthquakes continued, and the fear of possible collapses was more than well-founded. Fear could be read in the faces, silences, and the overall bewilderment of those people.

Among those people we tracked down the owner of the workshop, we explained to him what the problem was and he shrugged in response: he could not do anything, because he was afraid that the workshop, located in an old stone building, could collapse on him. However, when he saw our van overloaded with all those goods he understood the reason for our trip and changed his attitude, reassuring us: "don´t worry, we will make it one way or another".

He raised the shutter, ran into the workshop, took the irons necessary and then went to work, safely, in the same square. When he wasn´t bent over the bonnet, fumbling with belts and electrical components, it was because he had to go back to the workshop to get some spare parts – and always in a hurry. He finished the job, and while thanking him I asked to pay.

"Nothing," he replied, "You don´t owe me anything." His work, he explained to us, was to be considered his small contribution to the success of the trip.

We then went back on the road, this time with the newfound confidence and awareness of the responsibility we had. Our small van now had a sign that said: “Let´s help the earthquake victims”.

We crossed the areas hit by the earthquake, we saw flocks of sheep that wandered through the countryside without a shepherd, abandoned; we saw the parapets of the collapsed bridges and rubble, lots of rubble; at one point we came across yet another collapsed bridge. A few cars, with great difficulty, crossed the stream below. We waited for a while and then we decided to cross it too. I don´t know how we did it, but we managed, with Ciccio on the side telling me what the best manoeuvre was.

When we reached the road, after a few hundred meters, we punctured a tire. While we were changing the wheel, a gentleman approached us crying, and he asked us where we were headed. He told us that he had been looking for his relatives for two days and that he hadn´t found anyone yet. He then said goodbye to us while climbing on his white Fulvia, recommending us to go to Santa Ninfa, "because the town had not yet received aid".

We drove slowly, the van overloaded and with the rear wheels misaligned with the weight. After a few kilometres, on the uphill road, we saw a group of people running towards us. They had sensed that we were bringing something: we stopped and distributed some bread, some coats, canned goods, and sugar. Then, we decided to reach Santa Ninfa to hand everything over to the medical staff. Along the way, we stopped at a cattle trough to quench our thirst and fill a bottle of water. While we were carrying out this operation, an army off-road vehicle with some soldiers on board stopped next to us. We talked about the events, and they told us they hadn´t eaten since the day before. And Ciccio thought it best to give them our breakfast.

After a few kilometres through piles of rubble, we finally arrived at the tent city, which was set up on the muddy ground. There was also a field hospital and a few moments later a young doctor went towards us asking what we had brought. When she learned that we had powdered and condensed milk on board, diapers, baby food, sugar and talcum powder (essential items for children), a smile of joy appeared on her face and she immediately sent some boys to unload the van and take everything to the tent.

Ciccio, taken by enthusiasm, told me: "I´m staying here to help out". With great effort, I managed to desist him and we set off home, planning to come back later on with a new load of aid. Near Capo Calavà, we finally met a column of military trucks that proceeded towards the Belice Valley, with escort and flashing lights on.

Ciccio was dozing and I woke him up when we reached his home in Milazzo. When I arrived in Villafranca, it was nine in the evening and in the main square the priest was waiting for me, along with the owners of a local transport company, as well as some citizens. They asked me which path I had followed because they were about to leave to bring essential goods to the Belice earthquake victims.

Then I learned that they had to follow another route that did not directly reach the tent cities (they were blocked before arriving there), although they managed to leave the aid at a collection centre. Over time, I realized that perhaps I had been among the first to arrive from outside the province on the sites of the disaster. This is probably the reason why Ciccio and I have seen rubble, loneliness, so many disoriented people and little help – often distributed irrationally.

Nicola Di Pietro"

* Translated by Chiara Venuto